Prosecutions & Trials (2011)

The starting point for setting in motion a prosecution is when an Investigation Paper (IP) is opened. An IP must be opened ‘once a [First Information] report is classified as a crime’. The figures are uncertain since an IP may be counted more than once as the file may pass between the police Investigating Officer (IO) and prosecutor several times (as the prosecutor may advise the IO to conduct further enquiries).

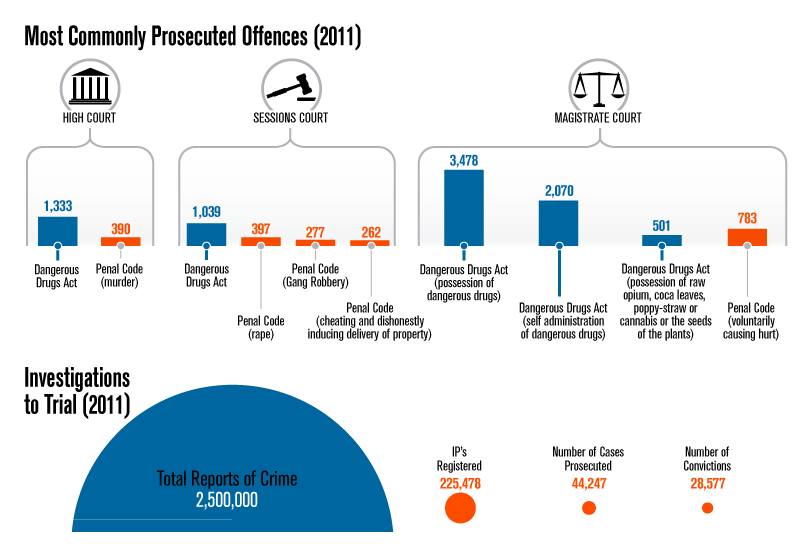

The analysis provided by the Prime Minister’s Performance Management and Delivery Unit (PEMANDU) indicates that ‘of the 2.5 million crimes reported in 2009, less than 10% resulted in the charging of a suspect and only 5.6% reached a verdict.’

The disparity in total reported crime and total number of IPs registered may be due to a number of factors – such as:

a) the initial report does not disclose a criminal offence (NOD); or discloses a civil or quasi-civil action and referred to the Magistrate (RTM);

b) initial investigations are inconclusive and result in a finding of No Further Action (NFA);

c) the report is referred to other agencies for action (ROA), such as the immigration department.

In 2003, of 1.9 million reports to police, 255,733 (13%) were investigated by police. In 2011 as depicted in the graphic above, of 2.5 million reports, less than 10% resulted in IPs being opened.

The difference between the IPs registered (225,478) and IPs resulting in prosecution (44,247 - i.e. 20%) again may have a number of explanations:

a) the policy of the prosecution department is not to prosecute unless there is a 80% chance of securing a conviction on the face of the IP;

b) the accused has not been arrested;

c) the matter is still under investigation.

The relationship between police and prosecutors appears attenuated: police detect, arrest and investigate – and prosecutors prosecute in court notwithstanding amendments to the CPC further to the recommendations of the Royal Commission and introduction of ‘district prosecutors’.

The closer integration of ‘investigation and prosecution …to enhance process effectiveness’ as practiced in other countries (where prosecutors sit in the police station to offer ready advice to police officers) appears not to be in place. The ‘control and direction’ of the prosecution is taken out of the DPP’s hands and efforts to enquire after an IP that appears to be dragging or to question the provenance of an IP several years after the offence was committed are seen by police to be impertinent.

The audit team note that in 2005, the Royal Commission report on the police found that the Chemistry Department was ‘overloaded’ with cases. The situation in 2012 suggested the Chemistry Department remained under pressure and delays in IPs were due to the volume of matters sent to the few chemists available.

There were indications that some DPPs saw their role to secure convictions, rather than to act in the public interest to administer justice impartially. This latter view is clearly stated in the draft Code of Conduct for Prosecutors. This appears to be supported by the superior courts views on disclosure. Amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code include a duty on the prosecution before the commencement of the trial to deliver to the accused a copy of any document which would be tendered as part of the evidence for the prosecution. However the Federal Court has ruled that this provision excludes witness statements. Disclosure is seen as ‘protecting criminals’. In other jurisdictions, full disclosure more often reflects the strength in the prosecution case and, advised by counsel, defendants will enter a guilty plea, especially where there is an incentive to do so (i.e. a reduced sentence).