Source Documents

Justice System Description

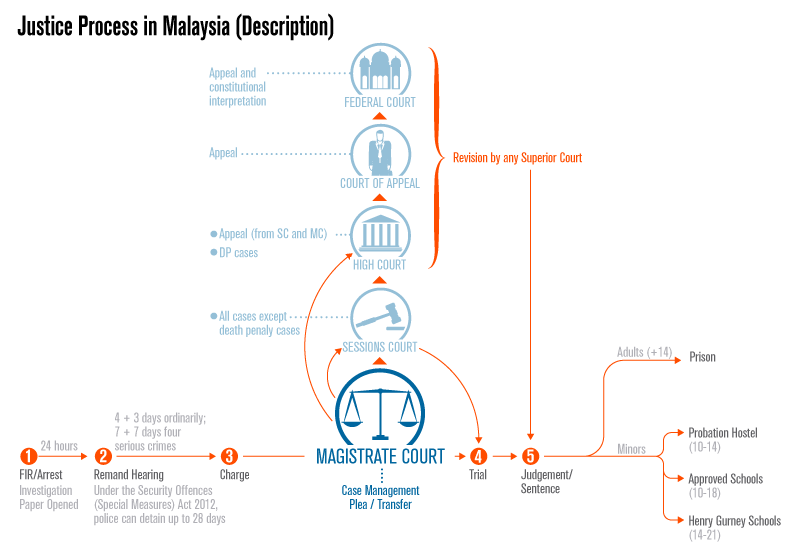

Criminal Justice Process in Malaysia

Slide (1) seeks to set out in a simplified format the criminal justice process in Malaysia for the year 2012. It tracks a case from the arrest stage through to ultimate disposal. It sets out the key events an accused person would go through in the criminal justice process: arrest, remand, charge followed by a screening or management mechanism that assigns the case to the relevant court or sets the matter for trial and appeal.

Arrest and Remand

After a person is arrested, there will be a remand hearing in court (within 24 hours after the arrest) to determine whether the person is to be detained under remand (custody may be under the prisons or police) pending police investigation or released on bail. For offences which are punishable with imprisonment of less than 14 years, the police can ask for an initial period of four days on the first application to complete their investigation prior to charge with a possible further extension of three days on the second application. For offences which are punishable with death or imprisonment of 14 years or more, the detention shall not be more than seven days on the first application and not more than seven days on the second application. During this time, an Investigation Paper (IP) is opened by the Investigating Officer (IO) who forwards the completed IP to the Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) for review. The DPP may refer the IP back to the police for further investigations to be made, or indicate that the case discloses a civil action rather than a criminal offence (there are a number of permutations), but where a matter discloses a criminal act, a charge is framed and the file will be sent to court.

Preventive Detention Laws

The law enforcement agencies may also invoke a range of preventive detention laws where there are reasonable grounds. For example, under the recently repealed Internal Security Act 1960 [Act 82], the police had the power to detain the accused for up to 60 days after which the Home Minister can sign a detention order for two years, and extend it after that (without going through the courts). A court in the High Court in Kuala Lumpur is dedicated to hearing ‘habeas corpus’ applications from those with the means to retain counsel to argue for them.

These laws were recently reviewed and the passing of the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 [Act 747] removes the police’s right to detain a person without trial, and reduces the maximum detention period from two years to 28 days. The repeal, however, will not affect those who have been detained earlier under the law.

Police Investigation and Charge

When a case is being investigated by the police, an Investigation Paper (IP) will be opened by the Investigating Officer (IO) who then forwards the completed IP to the Deputy Public Prosecutor (DPP) for review. The DPP may refer the IP back to police for further investigation to be made, or indicate that the case discloses a civil action rather than a criminal offence. However, where a matter discloses a criminal act, a charge is drafted and the file is sent to court.

Case Management

The person is then charged with an offence and the case will be ‘managed’ by a senior magistrate. The accused may be released on bail (after the bail bond has been executed) or be held under remand (and will be transferred to a prison).

If the subject matter is too serious and complicated to be heard in the Magistrates Court, it will be transferred to a higher court (where the judge in the Sessions Court or registrar in the High Court will take over the processing of the matter). Magistrates deal with a wide range of matters from administrative summons and traffic offences to juvenile and adult crime. Each case is referred to the appropriate court. For example, in the case of juvenile crime, the Magistrate will sit in the Court for Children).

Trial and Judgment/Sentence

In matters concerning general crime (including drug offences) where a guilty plea is entered, the matter is swiftly disposed of. If the accused refuses to plead or does not plead or claims trial, the case is set down for trial. Cases are generally heard in two parts. Firstly, at the close of the prosecution case, the defence (where represented) may make a submission of no-case-to-answer and the case is adjourned (usually in the Sessions Court and High Court) for the courts to consider the arguments. Secondly, where the defence submission fails and a prima facie case is made out, the trial continues and the accused will be called to enter his defence. At the conclusion of the trial, a judgment is entered. Judgments are entered immediately in the Magistrates Court; however, in long or complex cases in the Sessions Court/High Court, a longer time would be required.

There are several methods of disposals available to the courts, which are acquittal and discharge, conviction and sentence or discharge not amounting to an acquittal (DNAA). Application for DNAA is requested by the DPP before the close of the prosecution’s case if the charge is groundless where the evidence is insufficient at present or where investigation is incomplete but may be strengthened later (Section 254 Criminal Procedure Code). The charge can be revived at a later date.

Appeals and Revision

Once judgment is entered, either party (DPP or defendant) may appeal the case up to the High Court (from the lower courts) and to the Court of Appeal (with leave, from the Sessions Court). The High Court or Court of Appeal have the power to revise the decision made in the subordinate courts and order the court to set aside the ruling and substitute its own (for instance, where a judge or magistrate has allowed a defence submission of no-case-to-answer at the close of the prosecution’s case, the reviewing judge in the superior court can set aside the ruling of the judge/magistrate and order the case to proceed and call for the accused to enter his defence).