Source Documents

Challenges

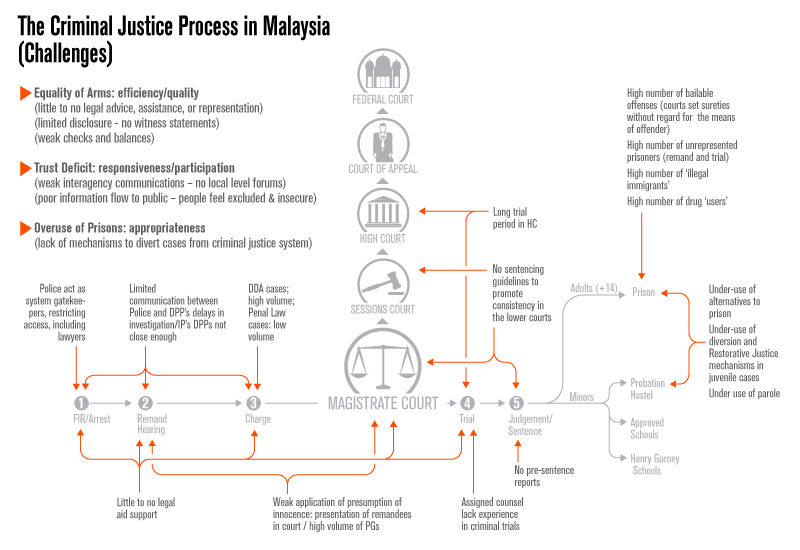

The Justice Audit found that the reforms to case management have improved efficiency in the way courts do business. What is less apparent is how the improvements in efficiency impact on the quality of justice delivered. Slide (3) summarises the challenges identified across the system in the form of checks and balances needed to guarantee ‘fair’ play so that everyone is guaranteed equal treatment under Article 8 of the Federal Constitution.

Equality of arms: Figures suggest 80% of persons on remand and 95% of those tried ‘lack legal representation’. At the same time, figures from the Magistrates’ Courts show 64% cases end in guilty pleas. The inference is that, presently, the scales of justice appear to be balanced heavily in favour of the state.

Responsiveness/participation: A popular perception is the ‘ineffectiveness’ of police and prosecution in detecting and prosecuting crime which results in ‘only a few of the crimes actually reaching the courts.’ Practitioners observed that people were prone to make complaints to police about ‘anything from the loss of an identity card to a missing cat’; that the public was ignorant of the law, justice process or policy decisions on whether or not to proceed with a case.

Communication between agencies appeared limited to occasional (once or twice a year) meetings between departmental heads (police/prosecution) or superior and subordinate judges/magistrates (to review judgments and matters of procedure). The system does not appear to be joined up: police arrest and investigate, prosecutors review and prosecute, magistrates/judges try the matters in court, prisons hold prisoners and supervise parolees. There also appears to be a deficit in legal awareness strategies that explain the law and legal process to ordinary citizens.

Public perceptions of crime and safety: The report of the Royal Commission on the police (2005) found that 89% of respondents were ‘worried to extremely worried’ about the occurrence of crime in their neighbourhood. In 2010, 97% Malaysians said they felt ‘unsafe’ which prompted government to make ‘crime reduction’ a National Key Result Area for the 1Malaysia programme. On the other hand, violent crime in Malaysia appears low (see: Violent Crime, slide 4 below). The audit was not able to interrogate further the causes of public disquiet or popular perceptions of the justice system.

Independent figures suggest the ratio of police to public is 1:270 (i.e. about one officer for every 270 persons). These police officers are then supplemented by 2.8 million RELA volunteers (i.e. about 1:10). However, whether the presence of RELA volunteers is a source of reassurance to the public or not, is not known.

Overuse of prison: Sentencing alternatives to prison are limited (see under Prisons below) and compliance monitors (i.e. probation officers – see under Juvenile Justice below)) are few. In line with sentencing policies elsewhere (applying, for instance, principles of ‘restorative justice’ in sentencing practice), prison figures indicate alternatives to custody could attach to many of the 50% of the sentenced population currently serving terms less than 5 years (and so at the lower end of the criminal scale). This serves the vision of the prisons for 2020 (to reduce the prison population) but might require a review of current sentencing policy and practice as well as a review of the available resources to monitor compliance.

Women occupy 4.7% of the prison population (1,599 women prisoners). Since women seldom constitute a risk to public safety or security, they are often deemed particularly suitable for alternative sanctions to imprisonment.

Police are the gatekeepers of the criminal justice system. At present, they appear to manage the caseload alone without the advice of Deputy Public Prosecutors (DPPs), or the check/balance provided by a defence lawyer. It is unclear what oversight mechanisms are in place to ensure compliance with Article 5 of the Federal Constitution (governing freedom from arbitrary detention and right to access a lawyer promptly on arrest).

Preventive detention laws are described as a ‘convenient short cut’ to crime solving. In September 2011, the Malaysian Prime Minister announced the decision to review its security laws, which includes the repeal of the Internal Security Act 1960, Banishment Act and the Restricted Residence Act. The Prime Minister stated in his 2012 budget speech: ‘Policing in a modern and open society requires laws to be repealed, amended and a new framework formulated to strike a balance between national security and individuals’ rights. Policing philosophy introduced during the insurgency is no more relevant.’ See: Legal advice and assistance below.

As at December 2011, there were some 3,000 detainees held under the preventive detention laws. Approximately half of the detainees have been released since the announcement while the other detainees’ status is under review at present.

The use of diversion mechanisms (often applied in juvenile matters and in appropriate cases involving adults, such as envisaged under the compounding provision in section 260 Criminal Procedure Code) appear all but absent. The use of mediation in general appears to have made an uncertain start (see Courts below).

Limited communication: The relationship between police and prosecutors appears attenuated - see Prosecutions and Trials below. The frequent use of discharge not amounting to acquittal (DNAA) can lead to a legitimate sense of grievance among persons accused years later of an offence long forgotten.

Local level forum: The compartmentalizing of roles appears to spread across the justice system, so that each institution becomes a silo accountable only to itself. The tri-partite meetings between police, prosecution and Bar have been discontinued. There appears no forum for the various institutions to meet whether at the local, regional or national level, unless at the highest levels of state. Improved communications across the agencies and involving the participation of all actors (including business people and local NGOs) serves to improve co-ordination and co-operation in preventing or tackling a pattern of offending that may be an issue in that locality (such as snatch theft in Kuala Lumpur, housebreaking in Penang, cheating in Melaka, or narcotics crime in Terengganu. )

Case categorization: It was not possible to ask the police why the volume of Dangerous Drugs Act cases appeared to be disproportionate to other categories of crime. It was the view of members of the bench and prosecution division that such cases were easier to prove (supported as they were by laboratory reports and urine tests).

Legal advice, assistance or representation: Article 8 of the Federal Constitution entitles everyone to equal protection of the law. A National Legal Aid Foundation has been established and put in funds (RM 15 million), however it was not yet operational at the time of the audit. The Bar in Peninsular Malaysia operates a Legal Aid Centre in each State offering walk-in services, dock brief representation and prison visits with the assistance of chambering students and lawyers offering their services for free. The Law Societies of Sabah and Sarawak provide their own services (Sabah offers legal aid clinics on Saturday and representation in court for bail hearings and guilty pleas). The location of the Legal Aid Centres, lack of resources and low numbers of available lawyers limit outreach – see Legal Aid Cases below.

The NLAF at the time of the audit may be challenged to provide national coverage since most lawyers are located in the state capitals (74%) and only 500 (out of 14,000) have signed up to the scheme. In addition, the proposal to insert ‘duty solicitors’ into police stations may require a paradigm shift in police culture and practice (away from the ‘run-around’ routinely given to lawyers appearing at the police station on behalf of their recently arrested client) . Memoranda of Understanding and Standing Orders may not prove adequate without the backing of primary legislation and close enforcement by the superior courts. A procedure to introduce ‘plea bargaining’ is about to be gazetted and is likely to raise questions of ‘due process’ (i.e. fairness) where the interests of the accused are not adequately protected by counsel.

In the High Court, it is the general rule that accused persons are represented (whether privately or assigned by the court) as the cases tried may involve the death penalty. In the subordinate courts, ‘most’ accused appearing in the Sessions Court are represented (according to judges), while in the Magistrate’s Court, representation appears to be the exception. Legal advice/assistance at pre-trial stage appears de minimis.

Presumption of innocence: The number of guilty pleas entered by unrepresented accused persons is high. Responses from sentenced and un-sentenced prisoners were that they were advised to enter guilty pleas (whether by the police to avoid delay, unnecessary costs, or obtain lesser sentences; or probation/social welfare officers to young people “to get the case over with more quickly or to gain the benefit of a lesser sentence” – without any impartial advice on the merits of the instant case or the consequences of a criminal conviction.

Notwithstanding amendments to the Criminal Procedure Code requiring the prosecution to deliver to the accused ‘a copy of any document which would be tendered as part of the evidence for the prosecution’, the Federal Court has ruled that this excludes witness statements.

The appearance of statutory ‘innocence’ is further open to question when detainees are brought in prison clothing and/or stand, manacled, before the Bench and suggests court and law enforcement officers are unfamiliar with international standards.

Prisons: The prison system currently operates within overall capacity. However, pressure is apparent in eight prisons – the most congested being Tawau in Sabah (see Prisons below). The proportion of prisoners on remand on bailable offences is 13% of all prisoners. All those interviewed stated they could not afford the bail terms set by the court. One senior prison officer commented: ‘sometimes it seems like the prison is for the poor’.

Access to legal advice / representation for remand and un-sentenced prisoners was limited to the few who could afford a lawyer (see Prisons below).

Access to legal representation for sentenced prisoners was reported to be guaranteed in High Court matters (court assigned counsel) but less available in the subordinate courts (see Prisons below). It follows that advice on lodging any appeal was also limited to those with the means to retain counsel.

Other significant categories of offender are foreign nationals and persons charged or sentenced under the Dangerous Drugs Act. As concerns the latter category, some 95% have been convicted of using drugs or being in possession of drugs (i.e. at the lower end of the scale).

Alternatives to prison: The Prison administration intends to reduce the prison population serving their terms behind prison walls by two-thirds by 2020. Early release schemes such as parole have been in effect since July 2008 and other schemes are being applied, such as: compulsory attendance, correctional centres and half-way homes - but figures are low for each of these – see Prisons below.

The Director General of the Prison Department indicated that the service was going through a process of transformation into a corrections service. In other jurisdictions this is accompanied by a change process that is signaled by a move from an overtly military to a more civilian style (reflected in symbolic alterations to uniform and increase in numbers of vocational training staff and civilian expertise) and towards a security approach based on principles of ‘dynamic’ rather than ‘static’ security (based on a co-operative approach between staff and prisoners). Such a move is not in currency at present.

Pre-sentence reports: Young persons in conflict with the law are sentenced after consideration of ‘pre-sentence reports’ which one magistrate commented on as being ‘very helpful’. Pre-sentence reports are not extended to adult offenders, even where they are unrepresented. The role of the probation department appears to be limited and the resource and expertise it can provide under-used.

Sentencing guidelines and practice directions: The sentences handed down in the subordinate courts are reported to be inconsistent (according to prison officers who noted disparities in prison sentences for like offences). Sentencing guidelines for common or garden offences (in the form of tariffs) are not issued by the superior courts which would assist magistrates in particular where they have to learn ‘on the job’. As a matter of sentencing principle, some sentences appear disproportionate and anomalous in the context of contemporary Malaysia. Practice directions on procedural matters such as bail are also absent.

High Court delays: While delays in the system have been reduced, they continue in the High Court and a waiting period of two years appears common. Some of the causes of delay are attributed to resource constraints, especially as concerns delays in chemists’ reports (there is one laboratory covering the north of Peninsular Malaysia and the prosecution department report that delay from the chemists can delay proceedings by 3-6 months).